With the recent reinvigoration of protest in the US against racially motivated police violence, a documentary like Patrick Vanier and co director Marie Naudascher’s Morri Na Mare (I Died in the Mare) proves as timely as it is heartbreaking.

With the recent reinvigoration of protest in the US against racially motivated police violence, a documentary like Patrick Vanier and co director Marie Naudascher’s Morri Na Mare (I Died in the Mare) proves as timely as it is heartbreaking.

The film is set in one of Rio De Janeiro’s most notorious favelas, the ‘Complexo Da Mare’ – a slum in which cyclical and unrestrained drug and gang violence is matched only by police responses of reckless, excessive and often indiscriminate brutality. Filming took place in the milieu of the heightened, varied protests surrounding the FIFA 2014 World Cup – and federal responses of police militarization, still in operation today and ‘indefinitely’. However, Vanier focuses upon the most tragic collateral damage resulting from the seemingly endless stalemate between ‘problematic’ slum culture, popular-held prejudice and inordinate police measures: the children.

The film documents the students of The Uere; a small, grass-roots afterschool program that functions as a safe house for Mare youth caught in civilian vs. state crossfire. There alone, kids are free to discuss not only their darkest nightmares but also their undying dreams. And, it’s the later – tended in The Uere and captured in the film – that currently constitute their only ticket out.

The film documents the students of The Uere; a small, grass-roots afterschool program that functions as a safe house for Mare youth caught in civilian vs. state crossfire. There alone, kids are free to discuss not only their darkest nightmares but also their undying dreams. And, it’s the later – tended in The Uere and captured in the film – that currently constitute their only ticket out.

Where are you from?

I’m French, born in Rouen in 1973. I moved to Paris for my studies at The Sorbonne.

What did you study?

What did you study?

I studied History. My MA thesis was about Italian national conscience construction.

How did you get into filmmaking?

I began writing for an interactive agency, mainly CD-ROM and website work. Then, I created a multimedia agency with associates Pepper Only and later with AtomiZ, working with video. I decided to leave France and this business. In 2001, I went on a yearlong journey through Australia and then India. I began to film people without intention, just an interest about their hopes and dreams – filming and talking with people about such topics.  I moved to Central America where for four years I worked as a cameraman with an English director called Mischa Prince. I worked mainly in Guatemala, on indigenous and social issues. Specifically: indigenous rights after the civil war, the exhumation process of war victims and about young people attempting to exit gangs – a very serious matter in Guatemala. Guatemala City is one of the most dangerous in the world for gang and drug violence. Working with vulnerable people in places with few rights and a very low legal presence was fundamental to my personal projects. I began my own documentary project with kids from the ghettos of Guatemala City; spending time with them, developing relationships, filming them.

I moved to Central America where for four years I worked as a cameraman with an English director called Mischa Prince. I worked mainly in Guatemala, on indigenous and social issues. Specifically: indigenous rights after the civil war, the exhumation process of war victims and about young people attempting to exit gangs – a very serious matter in Guatemala. Guatemala City is one of the most dangerous in the world for gang and drug violence. Working with vulnerable people in places with few rights and a very low legal presence was fundamental to my personal projects. I began my own documentary project with kids from the ghettos of Guatemala City; spending time with them, developing relationships, filming them.  The filming was abruptly stopped when two young kids were killed in front of a local school. They were friends of one ex-gang member’s girlfriend, and were murdered for it, in a revenge homicide. The school director wanted to protect her students from potential repercussions due to my filming. But, a few hours after the double murder, I was filming. Nobody was crying. A six year-old boy explained to me that this was because there is no time or place for mourning in the favela. I learned a lot about the conditions of marginalized children: poverty, prejudice, and criminalization of poverty. In such conditions and places there exist very few chances to change your destiny, as well as the heavy weight of your birthplace within society, i.e., the social/structural view of ghetto youth as “gangster seeds” and the attitude of “best kill them young”.

The filming was abruptly stopped when two young kids were killed in front of a local school. They were friends of one ex-gang member’s girlfriend, and were murdered for it, in a revenge homicide. The school director wanted to protect her students from potential repercussions due to my filming. But, a few hours after the double murder, I was filming. Nobody was crying. A six year-old boy explained to me that this was because there is no time or place for mourning in the favela. I learned a lot about the conditions of marginalized children: poverty, prejudice, and criminalization of poverty. In such conditions and places there exist very few chances to change your destiny, as well as the heavy weight of your birthplace within society, i.e., the social/structural view of ghetto youth as “gangster seeds” and the attitude of “best kill them young”.  After a personal brush with endemic violence – some men opened fire on my girlfriends’ car – I moved to La Paz, Bolivia… to get some peace. I continued my work concerning indigenous rights and covered the election of the first indigenous president in Latin America since colonization. I worked as a foreign correspondent and filmmaker for five years in the Andes.

After a personal brush with endemic violence – some men opened fire on my girlfriends’ car – I moved to La Paz, Bolivia… to get some peace. I continued my work concerning indigenous rights and covered the election of the first indigenous president in Latin America since colonization. I worked as a foreign correspondent and filmmaker for five years in the Andes.

What is your connection to Brazil?

I have some Brazilian friends and had the opportunity to visit Brazil several times while in Bolivia. Altiplano to Ipanema is always good for your mind and soul. I decided to move there in mid 2011, to join a Brazilian photographer and open up the spectrum of my topics.

How did you come to work with your co-director?

How did you come to work with your co-director?

I knew Marie Naudascher when I arrived in Rio. She is a French journalist based for five years now in Rio. She works mainly for radio, and she has just finished a book about Brazil. She has deep knowledge about the country and it’s issues. We covered the main social issues in Rio in 2013: the huge protests against rising prices of transportation, against corruption, and finally against the 2014 World Cup. People in the street were begging for schools and hospitals in FIFA standards, people were fighting for the basic rights of education and healthcare.  During theses days of protests, we went to the Complexo da Mare. In the morning of the same day, June 12th, 2013, one military police officer and thirteen people of this favela died. No confrontation – most of the victims were shot inside their own homes or in the street. The military police’s violent tactics are strongly denounced by the Mare people and by the human rights movements.

During theses days of protests, we went to the Complexo da Mare. In the morning of the same day, June 12th, 2013, one military police officer and thirteen people of this favela died. No confrontation – most of the victims were shot inside their own homes or in the street. The military police’s violent tactics are strongly denounced by the Mare people and by the human rights movements.

How was the film funded?

To produce the short documentary, we participated in a Crowd Funding organized by the Investigative Agency based in Sao Paulo: A Publica http://apublica.org/ . Sixty projects were selected by the agency and twelve were selected by the donors. We get Rs 6000 for the whole project (US$ 2700 ).

Why did you decide to focus on the effects of violence on children?

Why did you decide to focus on the effects of violence on children?

My experiences in Guatemala were important; I was never able to finish my work there after the school murders and was very frustrated. As you can imagine, a Brazilian favela is always full of children playing, running around. Marie knew about the Uere Project featured in the film – a program for violence-traumatized children – before this tragic day. So, it became clear to  work together and focus on the impact of the endemic violence, its invisibles traces, the fears, the experiences of the children. How kids can manage violence. As I saw in Guatemala, children stand before the violently murdered, before corpses in the street. What are they learning? The other goal is to declare that poor/black/marginalized children in Brazil deserve the same rights as others kids. The prejudice against black slum children is still strong, and they really have no hope or motivation to stay alive, no equal opportunity. The “gangster seeds”. It’s so much for a little kid to manage life between the crossfire of drugs traffickers and hostile, violent, military police intervention.

work together and focus on the impact of the endemic violence, its invisibles traces, the fears, the experiences of the children. How kids can manage violence. As I saw in Guatemala, children stand before the violently murdered, before corpses in the street. What are they learning? The other goal is to declare that poor/black/marginalized children in Brazil deserve the same rights as others kids. The prejudice against black slum children is still strong, and they really have no hope or motivation to stay alive, no equal opportunity. The “gangster seeds”. It’s so much for a little kid to manage life between the crossfire of drugs traffickers and hostile, violent, military police intervention.

Have you been following, and do you care to comment upon, any parallels with what’s happening in the States now? I.e. Trayvor Martin, Michael Brown, Ferguson and the race riots against racial profiling – how these may add another layer of significance to your documentary?

Have you been following, and do you care to comment upon, any parallels with what’s happening in the States now? I.e. Trayvor Martin, Michael Brown, Ferguson and the race riots against racial profiling – how these may add another layer of significance to your documentary?

I think we can establish a parallel. It seems that the behavior of the US and Brazilian police forces in poor neighborhoods are to an extent comparable. Also, it appears that the police in the US are acting on the same racial prejudice.  In both countries, racial matters have an impact upon people’s rights. This is not new, but in the last months in both countries, events have highlighted this problem. http://www.bbc.com/news/blogs-trending-29051415 And, when groups question this point, the use of excessive, even military force against them can become automatic. No dialogue. So, yes, perhaps my film will resonate with people in the US.

In both countries, racial matters have an impact upon people’s rights. This is not new, but in the last months in both countries, events have highlighted this problem. http://www.bbc.com/news/blogs-trending-29051415 And, when groups question this point, the use of excessive, even military force against them can become automatic. No dialogue. So, yes, perhaps my film will resonate with people in the US.

Do you know the statistics: how many injuries/fatalities do the children in the Mare face per year, how long has this violence been present?

Do you know the statistics: how many injuries/fatalities do the children in the Mare face per year, how long has this violence been present?

It’s hard to find statistics, monthly some kids are killed by the Military Police. Very rarely is there due process. A decent resource for statistical information may be: http://gvnet.com/streetchildren/Brazil.htm

What was it like filming in tenuous moments of ‘peace’?

Complexo da Maré is a huge slum, 130,000 people. Several Drug Gangs own the territories, fighting amongst themselves and against the police. The violence is an issue night and day, sometimes more, sometimes less.  We spent two months in Mare, mostly in the school. This period was tense for the kids and staff. To avoid endangering the kids, we decide to follow the rules of Yvonne Bezerra de Mello, the woman who runs the program: no filming outside or around the school, no contact with kids outside the school (some kids’ families are involved in the drug trafficking). Our intention was not to capture street violence. We tried to focus on the kids and to catch what was happening through their eyes. Inside the school, the kids are slightly more relaxed. For them, it’s a more peaceful, safe place – often more so than their own homes. We maintained discretion around the school, which is why there are only few images of the day-to-day favela life.

We spent two months in Mare, mostly in the school. This period was tense for the kids and staff. To avoid endangering the kids, we decide to follow the rules of Yvonne Bezerra de Mello, the woman who runs the program: no filming outside or around the school, no contact with kids outside the school (some kids’ families are involved in the drug trafficking). Our intention was not to capture street violence. We tried to focus on the kids and to catch what was happening through their eyes. Inside the school, the kids are slightly more relaxed. For them, it’s a more peaceful, safe place – often more so than their own homes. We maintained discretion around the school, which is why there are only few images of the day-to-day favela life.

How else did you approach filming such a delicate subject?

How else did you approach filming such a delicate subject?

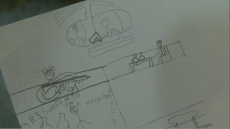

We had a strong empathy for the kids, as you can imagine. For them, we were double strangers. Not Brazilian, not from the community. But it was quite easy to forge collusion with them. We spent days without filming, with the camera outside of the bag but without filming them. Never hiding our intention but never objectifying them. When a real relationship was finally forged, the situation outside was critical, so the school asked us to stop our work for a time and to not focus on any individuals. The philosophy was that “pedagogy is collective, so you can’t isolate a kid”. We had to also attempt to avoid having these children tell their families about us, that a French team is working inside the school on the subject of violence. It could be very messy considering the fragile equilibrium of this community. This is why we incorporated drawings. The sketches are very revealing; metaphors without filter.

Despite the ‘collectivity’ edict, was there any particular child who really stood out for you?

Despite the ‘collectivity’ edict, was there any particular child who really stood out for you?

We had nice moments with a lot of kids in the school, mainly with one particular eight and a half year-old. We shared a lot of natural hugs with them. After weeks of our presence we were part of the classroom, laughing with them a lot. But maybe Daniel, who is playing football in the movie, made the greatest impact. He’s not part of the program but lives close to the school. He’s full of energy, is super-active, has a strong imagination and he engages the whole community: the cops, the drug dealers. As he said himself, he has no fear. In some ways he’s the most sympathetic because this little kid is possibly  the most in danger, much more than the kids of the school who are in transition to get new dreams and to find a way to change their destiny.

the most in danger, much more than the kids of the school who are in transition to get new dreams and to find a way to change their destiny.

So, in your view, is this program for violence-traumatized children truly effective, and in what ways?

I think this program is working well. Public schools in Brazil are only part time, so kids attend outside school’s curriculum. The pedagogy is based on several premises, but two are very important. The first is the possibility for the kids to talk about daily life, about love, and about the violence. At the beginning of each session, kids have the opportunity share strong stuff.  And the confident atmosphere of the classroom helps a lot. Another goal is the exercise of academic agility; kids have to be quick to answer some questions, calculation, math, and geography. The head of the school and the creator of the pedagogy is Yvonne Bezerra de Mello. She has a strong experience with street kids in Brazil and kids in conflict zones. You can find good resources about Uere Project and Yvonne here: https://www..ashoka.org/fellow/yvonne-bezerra-de-melo http://www.conti-online.com/generator/www/uk/en/contisoccerworld/themes/03_presscenter/01_pressnews/pr_2013_06_24_uere_interview_en.html

And the confident atmosphere of the classroom helps a lot. Another goal is the exercise of academic agility; kids have to be quick to answer some questions, calculation, math, and geography. The head of the school and the creator of the pedagogy is Yvonne Bezerra de Mello. She has a strong experience with street kids in Brazil and kids in conflict zones. You can find good resources about Uere Project and Yvonne here: https://www..ashoka.org/fellow/yvonne-bezerra-de-melo http://www.conti-online.com/generator/www/uk/en/contisoccerworld/themes/03_presscenter/01_pressnews/pr_2013_06_24_uere_interview_en.html

Is it government funded/supported?

The Uere Project is supported by private donors. Part of the school strategy is to not to be dependent upon the mistrusted State. Some private donors and some company support. You can find more details on the link: http://www.projetouere.org.br/

The Uere Project is supported by private donors. Part of the school strategy is to not to be dependent upon the mistrusted State. Some private donors and some company support. You can find more details on the link: http://www.projetouere.org.br/

It sounds like a valuable form of coping. But what of structural change aimed at concretely bettering the lives of the children? Is there an effective way to break the cycle of poverty – crime – violence and responses of excessive police violence, in areas like the Mare in Brazil?

In the beginning of April, the Federal Government sent in the Army to the Mare! http://agenciabrasil.ebc..com.br/en/geral/noticia/2014-04/federal-troops-occupy-slum-communities-complexo-da-mare  Instead of investing in education and infrastructure there, they sent two thousand soldiers with tanks. The objective was to secure the road between the international airport and downtown Rio, for the sake of the World Cup. A few days ago, the City of Rio asked the Federal State to extend this occupation until the end of the year. Since the end of 2008, the City of Rio is working on a program called the ‘pacification’ of slum areas, with the goal of ‘peace’. At this time, for me as an observer, it is very difficult to evaluate these policies. I’m uncertain if the lives of the people of the favela will be bettered. An interesting paper about the ‘pacification’ in slums in Rio and Mare: https://www.iiss.org/en/politics%20and%20strategy/blogsections/2014-d2de/may-b015/brazil-favela-3b61

Instead of investing in education and infrastructure there, they sent two thousand soldiers with tanks. The objective was to secure the road between the international airport and downtown Rio, for the sake of the World Cup. A few days ago, the City of Rio asked the Federal State to extend this occupation until the end of the year. Since the end of 2008, the City of Rio is working on a program called the ‘pacification’ of slum areas, with the goal of ‘peace’. At this time, for me as an observer, it is very difficult to evaluate these policies. I’m uncertain if the lives of the people of the favela will be bettered. An interesting paper about the ‘pacification’ in slums in Rio and Mare: https://www.iiss.org/en/politics%20and%20strategy/blogsections/2014-d2de/may-b015/brazil-favela-3b61  What I observed during my time in the Mare and in other favelas in Brazil is that change is only possible through education, justice and the elimination of corruption. The number of disappearances in Rio is high; some sources indicate 5000 people per year. The Military police are involved in many cases. During these last fourteen months of protest, people in the street were also asking for police demilitarization. Maybe it’s one first step to avoid civil war.

What I observed during my time in the Mare and in other favelas in Brazil is that change is only possible through education, justice and the elimination of corruption. The number of disappearances in Rio is high; some sources indicate 5000 people per year. The Military police are involved in many cases. During these last fourteen months of protest, people in the street were also asking for police demilitarization. Maybe it’s one first step to avoid civil war.

What are the effects upon or the consequences for a society when violence becomes institutionalized, especially violence that begets such collateral damage (violence against children)?

From what I’ve seen, the trivialization by Brazilian society of the violent approaches of the police and the State; the ‘institutionalization’ of violence – produces a psychologically ill society. Specifically, violence against slum children is an accepted norm in Brazil. An important part of Brazilian society supports State violence. Most who support it are from rich areas of Rio and have never even visited a slum; they have  no contact with people who exist marginally. This way, it’s easier to close an eye to tactics of excessive violence by the State, especially with the other eye open and locked on the torrent of sensationalist, mock-news that passes on the TV. I’m supposing that the violence becomes virtual for them. Even from within the favela, it’s hard to determine who is perpetrating the violence through direct drug/Gang activity or involvement, and who are the victims. And, outside the favela, this confusion is extended to include children. Easier for the wealthier Brazilian society to snap to the quick conclusion: slum kid equals drug dealer.

no contact with people who exist marginally. This way, it’s easier to close an eye to tactics of excessive violence by the State, especially with the other eye open and locked on the torrent of sensationalist, mock-news that passes on the TV. I’m supposing that the violence becomes virtual for them. Even from within the favela, it’s hard to determine who is perpetrating the violence through direct drug/Gang activity or involvement, and who are the victims. And, outside the favela, this confusion is extended to include children. Easier for the wealthier Brazilian society to snap to the quick conclusion: slum kid equals drug dealer.

Again, the parallels with the current US racial profiling controversy are unnerving. What did you hope to achieve in making this film?

Again, the parallels with the current US racial profiling controversy are unnerving. What did you hope to achieve in making this film?

This is very hard to say. An objective was to give voice to these children who are voiceless. A lot of people are afraid of slum people and even slum children – often without logical reason. However, as we saw in the Mare, these kids face real fears daily: of dying, of seeing their parents shot by the police or traffickers. Maybe the film can reverse some prejudices.

What are you working on next/now?

What are you working on next/now?

I’m working on two fronts: one personal project which has nothing to do with video, and the other one a documentary project about the body and its social representation throughout different places in the world. I hope to work on this new project with a very talented Brazilian documentary director. -Larissa Zaharuk View Patrick Vanier and Marie Naudascher’s documentary “Morri Na Mare” here: http://vimeo.com/89077880