Playgrounds are a cornerstone not only of childhood and childrearing, but also arguably of humanity. Inarguably, they are the proto-arenas where separation begins, identity is formed and socialization gets underway.

Playgrounds reflect the political and cultural identity of a nation. In the language of demographics, their absence, presence and general quality speak volumes regarding a city or district’s storied past and potential future – providing commentary as well upon the social contract between citizen and state.

A reflection of the collective us, playgrounds are an investment in our common destiny. As such, these often overlooked institutions merit closer inspection.

A reflection of the collective us, playgrounds are an investment in our common destiny. As such, these often overlooked institutions merit closer inspection.

Here to tell us what makes the best playground and why is landscape architect Clement Willemin; co-founder of innovative and award-winning French design firm BASE.

Are you from an artistic family?

Are you from an artistic family?

Yes, my Dad was a filmmaker. When I was a student, I worked in a puppet theatre. I consider myself a manual person – I believe sometimes that intelligence is located in the hands.

When did you know you wanted to be an architect?

I came to landscape architecture by chance after art school. I’d studied color and space in a generic mode. I tried a lot of schools after: film, fine arts, decoration, etc. The only competition I could do well was landscape architecture, although I could barely tell the difference between an oak and an ash tree. Still, I thought ‘this could be for me!’

Did any books, films, events or figures from your childhood inspire you?

Did any books, films, events or figures from your childhood inspire you?

I was always inspired by movies more than anything. John Carpenter had quite an impact on me when I was a kid in the ‘eighties. Films like Escape from New York or Christine have an impact even now. The sets are dark, dramatic and cool without being spectacular, without seeming uncommon or overwhelming – a kind of ‘common strangeness’ that I like.

What was your childhood relation to open spaces/nature?

What was your childhood relation to open spaces/nature?

I was raised in a very urban and interior world. I discovered the power of landscape through motorcycles. Riding a motorcycle is different from a car or a bicycle. You can really feel the outside ‘in your face’ but it also gives you an opportunity to understand terrain quickly – to get a clear, direct view of large territories. Potential discoveries as well as danger are always present, giving some intensity that you couldn’t experience otherwise. Every element is there: escape, risk, adventure, and exploration. All this – just a few kilometers from your own place.

Where did you go to school?

Where did you go to school?

After art school I went to Versailles, to The School of Landscape, and I liked that title very much. The school starts with a trip. The Chateau is right next to the school. The school grounds are the King’s orchards. Plus, you can meet amazing people there. This school is not like regular university. It is a unique cultural experience.

How did you come together with your partners?

We met at Versailles. After graduating, none of us were able to work for someone else in a regular practice – we had a bit too much character at that time. So we felt we had no other choice but to open a firm right away, which was quite scary. The main issue was networking, surviving, and accessing our first commission. I feel that, unlike in architecture, clients are willing to trust younger companies to create a garden. A garden can’t possibly collapse on itself, can it?

And, where have you built playgrounds since opening your design firm?

And, where have you built playgrounds since opening your design firm?

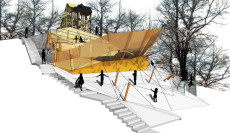

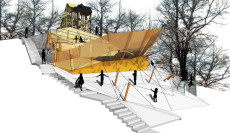

We made our first one in Champagne in 2007. Then the Paris Belleville playground opened in 2008 and was quite a success. In 2014, we finished several other ones, including a big wooden construction in Lyon, and a weird box in Bordeaux.

Which are you most proud of and why?

Which are you most proud of and why?

The latest playground in Lyon is 1000 meters-squared large. It is quite spectacular, but we also had some great construction companies working on it. In the end it has the scale of a big building, but it remains a surface.

None of them can be simply described, which might be one of their many draws. One can see them as places in which to get lost, to discover. Lormont has a public trampoline, which is quite a unique feature and not easy to design.

What is your firm’s unique approach or design philosophy?

What is your firm’s unique approach or design philosophy?

Concerning playgrounds, even if no vegetation is involved, we consider them pieces of landscape, or more precisely, as ways to look at and discover the landscape. We take risks. We try to propose spaces for the imagination of children – very different than ours, more powerful and abstract. Our playgrounds look like nothing precise, and we don’t intend that they do.

Nature is purely an environment for the playgrounds we make. It embraces it somehow, but children have a tendency to destroy vegetation in playgrounds. So we have to make it as separated as possible. At least, that is what we have been doing so far.

Drawn from your own childhood experiences, what makes a great playground?

Drawn from your own childhood experiences, what makes a great playground?

A playground should not be a fixed scenario, a simple and explicit figure or set. It should allow multiple interpretations. You have to be able to tell yourself different stories regarding the space.

Playgrounds are a cornerstone of childhood in the modernized west, to the extent that fashion model and philanthropist Natalia Vodainova felt motivated after the Belsan Massacre to create The Naked Heart Foundation – building ninety playgrounds in Russia – a country with previously few to none. What has motivated you?

In Europe, playgrounds as we know them are related to post World War II and a city’s reconstruction. They were often built on the ruins of destroyed territories and buildings.

Today, a cool playground is, in our eyes, the best service you can provide a district. They have the capacity to become for a society a real object of unity and also of collective pride.

Today, a cool playground is, in our eyes, the best service you can provide a district. They have the capacity to become for a society a real object of unity and also of collective pride.

Furthermore, for children, playgrounds represent an alternative to the enclosed worlds of family and school, and therefore a prefiguration of their future socialization. On a playground, you can freely meet and play with total strangers – scary and stimulating at the same time.

Which city/nation has the best/worst play grounds. Why?

Berlin has great playgrounds, made of spontaneous and crazy constructions that can seem almost hazardous but totally cool. Lots of cities don’t care for it. It’s a shame that every kid doesn’t have a decent place to symbolically escape his parents from time to time.

Yes, my son loves the one in the Berlin’s Tiergarten. In NYC, playgrounds are abundant but traditional; not works of art/innovation. They are often heavily gated with lots of metal, rubber, and plastic. What do you think is the solution?

Yes, my son loves the one in the Berlin’s Tiergarten. In NYC, playgrounds are abundant but traditional; not works of art/innovation. They are often heavily gated with lots of metal, rubber, and plastic. What do you think is the solution?

NYC definitely has a problem with its local parks and playgrounds, although The High Line is one of the most brilliant public spaces currently. I am sure that this trickle down into will change soon – either through the Berlin model, i.e., spaces made up by the people, or in the French mode – through public investment.

That’s funny because The High Line was apparently inspired by Paris’ Promenade plantee. What is the danger of neglecting to invest in spaces for children to play?

That’s funny because The High Line was apparently inspired by Paris’ Promenade plantee. What is the danger of neglecting to invest in spaces for children to play?

I would say the critical age is between eight and twelve, the pre-teen age. Nothing positive is usually provided for them – yet it is an age when social relations can become intense and violent. It is important that girls and boys continue to interact, to train their energy in a space conducive to this.

Sounds like your next project. What is your next project?

Sounds like your next project. What is your next project?

We are currently working on an exciting competition in Vietnam. The competition is a bit of a secret right now, but we’re studying a university campus in Hanoï. We are always happy to try out new climate conditions and study exotic plants!

And, speaking of next, what is the future of playgrounds?

Playgrounds might appear more important or more critical for cities in the future – if things don’t turn too bad! After all, the society of leisure is not the worst future for us. We should keep in mind that people are constantly changing and adopting new perspectives at a fast pace, especially concerning public space and the idea of sharing territories in life. In that respect, playgrounds can become a possible vehicle for projecting new ideas for new ways of living together, since children are indeed our future!

Playgrounds might appear more important or more critical for cities in the future – if things don’t turn too bad! After all, the society of leisure is not the worst future for us. We should keep in mind that people are constantly changing and adopting new perspectives at a fast pace, especially concerning public space and the idea of sharing territories in life. In that respect, playgrounds can become a possible vehicle for projecting new ideas for new ways of living together, since children are indeed our future!

-Larissa Zaharuk

To See more of architectural firm BASE work,: http://baseland.fr