The recent ISIL terror attacks in Paris challenge, among many other things, our Western false-notions of ‘safe distance’ from conflict.

The recent ISIL terror attacks in Paris challenge, among many other things, our Western false-notions of ‘safe distance’ from conflict.

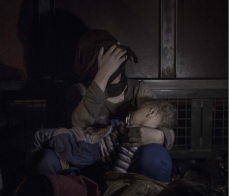

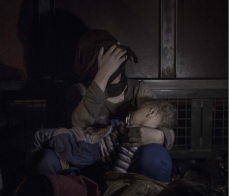

Magnus Wennman’s viral photo series Where The Children Sleep, which documents but a few of the over-one million displaced Syrians since 2011, is a timely reiteration of such fallacy.

The Swedish photojournalist’s images demand witness to what we no longer should, nor in this ‘technologically borderless’ world even can ignore, by focusing on the most vulnerable in the crisis, the children.

Wennman utilizes the premise of bedtime; its peaceful repose usurped by the basic struggle for physical and psychological survival amid the inhospitable diaspora into which these children have been helplessly flung.

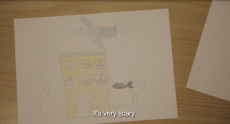

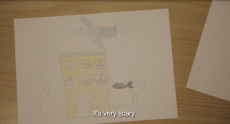

Following this up is the photographer’s foray into filmmaking; a redemptive documentary entitled Fatima’s Drawings – a first-person account of an inconceivable journey by the now-settled nine-year old protagonist.

Following this up is the photographer’s foray into filmmaking; a redemptive documentary entitled Fatima’s Drawings – a first-person account of an inconceivable journey by the now-settled nine-year old protagonist.

With the unwise, obsolete and dangerously insular rhetoric of would-be leaders like Donald Trump and Marine Le Pen finding a wide and willing audience in the world today, the voices of these children, and of the man who would not shut them out, are truly welcome.

As a child in Sweden, did you busy yourself with photography or with other media?

As a child in Sweden, did you busy yourself with photography or with other media?

I always knew I wanted to express myself visually. I was very interested in drawing and painting. When I was ten, I made oil paintings that I gave to all the relatives. As I grew older, I began to look up to the photographers, especially those of the major newspapers. At that time Jens Assur was the star. He has had great influence on many photographers in Sweden. I saved money to buy my own camera. Pretty soon, I knew it was the camera I wanted to work with and I decided to be a photographer at sixteen. I am lucky, I never had to think about what I wanted do when I grew up.

Were politics/news issues featured prominently in your upbringing?

Growing up, many of our friends were refugees and children of refugees. This has always been an important issue in my family.

Growing up, many of our friends were refugees and children of refugees. This has always been an important issue in my family.

Specifically, my mother and father divorced when I was very young and my mother remarried to a man who came with his family from Chile as political refugees. It has always been natural in my family to discuss policy regarding refugees and what they went through before coming to Sweden.

So, in a sense, Where The Children Sleep is a personal work.

What about travel, was your childhood full of travel?

I did not travel more than any other kid my age. My Dad worked, and still does, as a sports journalist. He traveled a lot all the time and I looked up to him very much. He was my biggest idol. I thought he had the coolest job in the world because he had to travel so much.

Your photojournalism has a very identifiable fine arts approach that gives it quite a unique graphic edge in that field. What did you study and where?

Your photojournalism has a very identifiable fine arts approach that gives it quite a unique graphic edge in that field. What did you study and where?

I did not study – I started working as a photographer when I was eighteen at the local newspaper Dala-Demokraten. Since 2001, I have worked on Scandinavia’s biggest daily paper Aftonbladet.

Without formal study, how have you evolved this aesthetic throughout your career?

Hard to say. I have always been open to try different cameras and techniques in my photography. I think that has led to the way I shoot today. For me, style is difficult to adopt – it’s a result of everything you have done and who you are. It is the journalistic part that I have had to evolve most over the years.

In what ways?

In what ways?

When I started working as a photographer at the newspaper nineteen years ago, it was important to be technically skilled – even as far as mastering the technology; developing pictures, sending pictures and so on. Being a photojournalist today is a different profession. You’re a journalist first, you need to be self-propelled with that aspect, as well as aesthetically and technically proficient in the photography aspect. The journalistic part has taken longer for me to develop and to find my way; to tell the stories.

You have told quite a story with Where The Children Sleep. Was it a ‘self-propelled’ endeavor or an assignment – or both?

You can say both. It was my idea and I did it as an assignment for my newspaper. I am very lucky to work as a staff photographer at a newspaper that knows the importance of good photojournalism.

You can say both. It was my idea and I did it as an assignment for my newspaper. I am very lucky to work as a staff photographer at a newspaper that knows the importance of good photojournalism.

What is it like; being out there documenting first hand not only the honorable but the horrible, i.e., helpless children as political collateral-damage?

The standard answer would be that you use the camera as a protection and that you have to turn off your feelings when you are working, but that is not the truth. Of course I take things in and I feel really sad sometimes.

The standard answer would be that you use the camera as a protection and that you have to turn off your feelings when you are working, but that is not the truth. Of course I take things in and I feel really sad sometimes.

And, what are some moments along the way in this story that really got to you?

From my experience, it takes a lot for a child to stop being a child, stop playing and laughing, but in some cases it felt like these children had to grow up too fast and become adults. A difficult moment to witness was when Hungary closed its border in front of thousands of families on their way through Europe. They stood on the doorstep of the EU but were simply not admitted. I talked to the families who had walked for weeks, their children foraging, picking apples from the trees, to eat. Families, children, forced to sleep outside of a four-meter high iron gate, just inches from the EU.

From my experience, it takes a lot for a child to stop being a child, stop playing and laughing, but in some cases it felt like these children had to grow up too fast and become adults. A difficult moment to witness was when Hungary closed its border in front of thousands of families on their way through Europe. They stood on the doorstep of the EU but were simply not admitted. I talked to the families who had walked for weeks, their children foraging, picking apples from the trees, to eat. Families, children, forced to sleep outside of a four-meter high iron gate, just inches from the EU.

Do you follow up with any of these families?

Do you follow up with any of these families?

I would love to follow up with all of them. I have just finished a short film called Fatima’s Drawings about nine year old Fatima, one of the children, who now lives in Sweden. It is a short film where Fatima herself explains and draw pictures of some of her experiences. I wanted to make one story which completely derives from a child’s thoughts and experiences about the escape from Syria. I worked with an animator to make Fatima’s drawings come to life in the film.

http://darbarnensover.aftonbladet.se/chapter/fatimas-drawings/

A gleam of redemption in the sadness. Why do you do this kind of work – keeping an open eye on often horrendous things that others can simply turn off – maintain a safe distance from?

A gleam of redemption in the sadness. Why do you do this kind of work – keeping an open eye on often horrendous things that others can simply turn off – maintain a safe distance from?

Because the alternative to not do anything is wrong.

In your own words, what was your pull to the story?

This is the most important story in our time.

-Larissa Zaharuk

To view more of “Where the Children Sleep” images here:

http://darbarnensover.aftonbladet.se/chapter/english-version/

To wiew Fatima’s Drawings here:

http://darbarnensover.aftonbladet.se/chapter/fatimas-drawings/

To view more of Magnus Weenmann ‘s work: @magnuswennman